During my first visit to Tokyo, on a business trip in 2016, I took a long walk in the lavish park that surrounds Meiji Shrine. It was a glorious Sunday morning and the inevitable crowds had not yet intruded on this island of calm at the center of the bustling metropolis. I was enveloped by the tranquility of the place when suddenly, maybe two hundred meters ahead, I spotted a gardener who swept the wide footpath using something like a grotesquely oversized broom. That tool must have been immensely heavy, with its long bamboo handle and the dense bristles of thick straw. Nevertheless, the groundskeeper’s elegant, swinging motions had an almost effortless quality to them. At a closer look, they reminded me more of a dancer moving to an inaudible tune, a painter skillfully applying a brush, or even a Samurai knight wielding their Katana sword. There was nothing “menial” about the labor of that gardener—quite the contrary, even a small crowd had already gathered to watch his performance in awe.

It instantly struck me that in most countries, people either ignore, or even look down with scorn or disdain, on the guy who’s “merely” sweeping the floors. In Japan however, that person is just as likely to be highly respected for the mastery they bring to their trade as an artist or an athlete might be. But what took me a lot longer to realize is that for the Japanese, this kind of social recognition is not actually the point.

Of course, positive feedback in the form of respect, honor, and fame feels pleasant to every person in every society. But whether we are awarded with these things or not is totally beyond our control, and that makes them dangerously short-lived sources for self-worth and wellbeing. The Japanese concept of ikigai, or “reason for being”, on the other hand puts our own subjective stance vis-a-vis our work at the forefront. Instead of relying on fleeting external validation, on money or fame, ikigai is much more concerned with how we personally, internally feel about what we do.

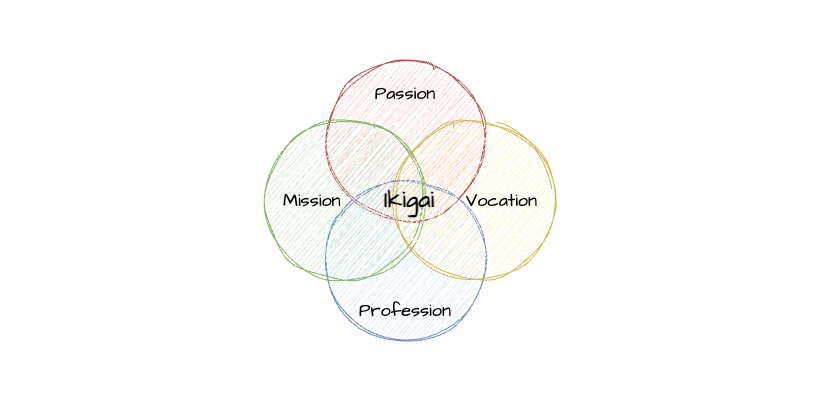

Ikigai, although hard to translate literally, is often circumscribed as the intersection of four elements: Passion, or jōyō, mission or shimei, vocation or shokugyō, and profession or shigoto. Do you enjoy what you do? Is your work aligned with your inner values? Does it have a positive impact on society? And, finally, are you good at it? If you can genuinely answer “yes” to these questions, chances are that you’ve already found your own, personal ikigai.

How you judge the relative importance of these components though is entirely up to you: Some people–like, one would assume, the groundskeeper of Meiji park–may rely more on their mastery of the craft, rather than on their love for the broomstick they’re wielding. Others might harbor a lively passion for bringing about societal change, say on a long-term issue such as climate action, but know that they will never actually be able to witness the results of their work.

Furthermore, ikigai doesn’t have to come solely from one’s full-time job alone. In fact, approaching paid labor with the expectation that it has to tick all those boxes to the utmost extent is a surefire way to set us up for disappointment. Instead, ikigai can be viewed as a colorful tapestry woven from employment, hobbies, family, volunteering, sports, and countless other activities. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter if you’re cleaning floors for a living, or writing short stories as a pastime, or reading books to the people at the old folks home, or if you’re running an entire country. What matters is that you look for, and cultivate, those bits and pieces scattered throughout your life which you can enjoy for reasons including passion, mission, vocation, and profession.