More than a year ago, I published this blog post about my daily routine. Since then I’ve received a lot of feedback, ranging from curiosity to mild encouragement to raised eyebrows. In essence though, the comments most people brought up boil down to three things:

- “This kind of lifestyle seems dull / repetitive / strenuous / masochistic. How do you find any joy in that?”

- “Isn’t it all just a fluke? Can you really keep these things up over the long-term?”

- “I see the point in what you’re doing, but I could never muster the motivation / willpower / determination to get started.”

So, today I want to clear up some confusion around these concerns. What seems to be in question is on the one hand how to create the momentum that’s necessary to establish positive lifestyle changes in the first place, and on the other hand, how that momentum can be sustained over the long-haul by turning things that we know we ought to do into things we want to do. As we shall see, these topics are tightly interconnected. But let’s try to tackle them one at a time.

On Pleasure

The issue of pleasure, enjoyment, and satisfaction, is in itself already a complex and multi-faceted one. The way I like to think about it is twofold: On the one side, I’m a believer in the Buddhist promise that pleasure can be drawn from the tiniest aspects of anything we do, famously including such exciting activities as chopping wood and carrying water. The basic idea is to focus on the joy that is available to us inside the present moment, rather than in some distant future. That may sound weird at first, especially coming from a guy who’s notoriously striving to improve. But consider the difference in attitude between attaching “satisfaction” to some future achievement (think: “I’ll be happy once I ran a marathon in under three hours!", “I’ll be happy once I’m married and have two children!", “I’ll be happy once I earn more than 100,000 Euro a year!") and the pleasure drawn from simple, everyday, moment-to-moment experiences (think: time spent in nature, connecting with another human being, eating a healthy meal). By focussing on the latter, every minuscule aspect of a mundane routine can become a source of happiness. Taken to the extreme, even hopeless or absurd situations can thus become bearable, even enjoyable. I tried to deepen this argument here, based on Albert Camus’ famous invitation that we should “imagine Sisyphus happy”.

Secondly, and this might be a bit easier to digest, I want to draw a clear distinction between the “simple” sensory pleasures that are available to us nowadays almost instantaneously (think: ice cream, chocolate, beer) and the more complex and deep feeling of being satisfied with some achievement that required dedication, effort, and skill. While, as we’ve seen before, you shouldn’t tie your happiness to an unknown (and, by definition, unknowable) future outcome, there’s no harm in enjoying the fruit of your hard labour once they begin to materialize.

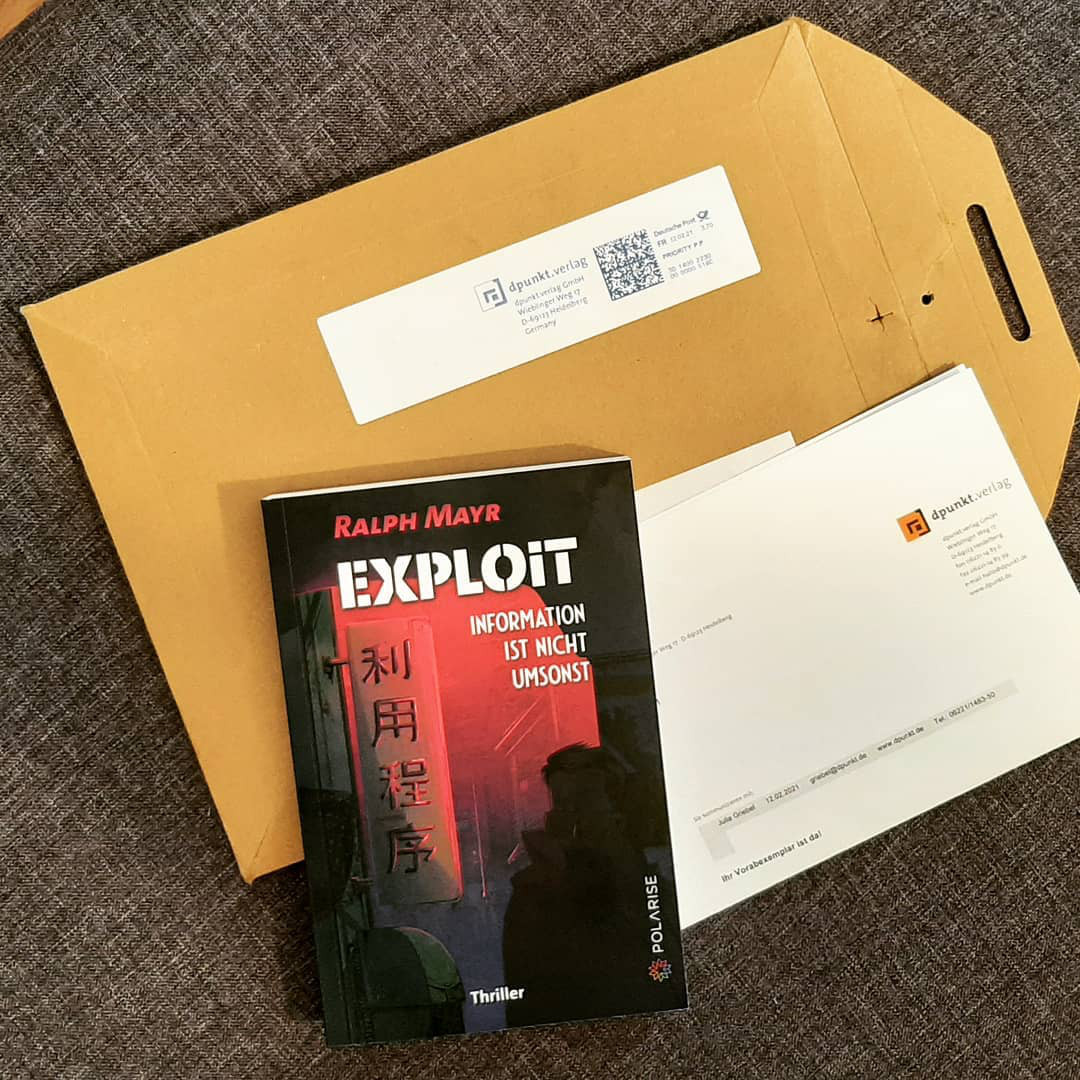

Take writing as an example: Even if you enjoy the process, it’s by far not always fun and games. Sitting down at that desk every day, even when you don’t feel like it, or when you’ve got better things to do, or when you just can’t think of anything to write anymore, isn’t always “pleasant”—even if you go full Zen on the present moment and all that. But months later, when you’re holding that first printed copy of what once was only an idea in your mind actually in your hands, fully aware of the countless hours you poured into it? Let me just say that that feels a lot better than any piece of chocolate I’ve ever had.

Copy #1 of my book, as it was mailed to me by the publisher.

On Sustainability

Let’s now turn to the next question, the one that’s been bothering me at the outset about almost any of the lifestyle changes I’ve made: “Will I be able to make this stick?"

In fact, I had picked up lots of supposedly positive habits in the past, only to drop them again on a whim—followed by the inevitable pangs of guilt because of my perceived lack of willpower. This is of course a vicious cycle that only leads to more and more disappointment and less and less self-esteem.

But reflecting on the things that did, in fact, stay with me over the long-term, such as running, journaling, or meditating, I found two techniques very helpful: First, plugging whatever it was I wanted to do into an already established daily routine. Meditation, for example, didn’t turn into a regular activity for me so long as every session required mental effort to get it started. But by making it a fixed agenda item as part of my morning and evening routines, there’s simply no question about when I’ll do it or if I’ll do it at all. Just like there’s no need to make a conscious choice about whether or not to brush my teeth before going to bed, there’s also no need to ponder about whether or not to sit down and meditate. It’s just something I do, every day, at a certain time. Period.

Secondly, with every new endeavor I try out, I set my initial expectations extremely low. And I mean comically low. My journaling habit for example started with the mere promise to myself that every day, I would write down exactly one line about one good thing that happened that day. Doing that took about 30 seconds, but after a few weeks it was established as something I would do regularly. Thus it was a lot easier to gradually expand the practice. These days, I write about a page per day, including thoughts and ideas for future blog posts, work-related considerations, observations about people I care about, and, of course, things that happened that day that I can be grateful for.

On Getting Started

But, and now let’s consider the third question often brought up: How did I even begin to embark on that journey of positive lifestyle changes? How did I get started?

I remember quite clearly when about ten years ago, while I was working a strenuous full-time job while at the same time being enrolled in an extra-occupational master’s degree program, I felt deeply dissatisfied with the state of my life. I spent about 40 hours a week at the office, ten at university, and on average another eight or so dealing with homework, study assignments, and group projects. My diet was a blend of chocolate chip cookies, coke, pizza, and beer. I smoked about half a pack a day and didn’t exercise at all. I slept badly and not enough, and was tired and exhausted all day. I wouldn’t refer to my mental state at the time as clinically depressed, but I was definitely far from being mentally balanced.

But the interesting thing is: Intellectually, I kew exactly what I would have to change in order to make myself better. It was obvious that (a) regular exercise, (b) better nutrition, and (c) improved sleep quality where what my body and my mind craved. In fact, I daresay that this simple diagnosis may be true for the majority of the population in our modern world, including many of the folks reading this. But being intellectually cognizant of what you should do and actually doing it day in, day out are two very different things.

So, how did I get from knowing to doing? Slowly. Gradually. And incrementally.

In cleaning up my life, I began with the very, very, very obvious thing to do: I quit smoking. That already was not only a huge step forward, but a first proof point for myself that change was, in fact, possible. Was it hard? Yes. Did I crave nicotine for months afterwards? Yes. Did my eating and drinking habits worsen at the time? Unfortunately, also yes. Was I pleasant to be around at that time? Probably not. However, quitting smoking was the foundation for everything that needed to follow. It took some months before my cookie and beer intake had even been back down to “normal” after I had my last cigaret. But at least, I now was rid of one of my demons, and I had learned an important lesson: I was capable of changing for the better.

With that confidence in mind, The next thing to tackle was sleep quality. Looking back now, it’s almost laughable how ignorant of my body’s most basic needs and its natural rhythm I had been back then: Imagine yours truly, hunched over a laptop at 10pm, nose about 5cm from the brightly glowing screen, munching on a Mars bar and pondering an engineering problem. Why, oh why wasn’t I able to fall asleep ten minutes later? And why didn’t I awake relaxed and ready to go in the morning?

Well, for starters, sugary treats immediately before bedtime should be an obvious red flag. Of course my glucose level would spike and my heart rate increase—the exact opposite of what you want to do in order to prepare your body for a good night’s rest. Next, staring into a brightly light screen right up until I was planning to hit the pillow? Another surefire way to sabotage a natural sleep rhythm. And finally, engaging in a cognitively challenging task, such as coding, is also not the best way to signal to your mind that it’s getting time to wind down.

It took me way too long to accept and act upon these facts, but once I started—again, incrementally—the benefits began to slowly accumulate. I would stop engaging with glowing displays (laptop, tablet, phone) about two hours before bedtime, instead grabbing an old-fashioned book or an e-reader without active illumination. I also restricted the times at which I was eating, in order not avoid a nightly insulin rush. Life hack: Since that time, I’m brushing my teeth immediately after dinner, thus making late-night snacking just a bit more… inconvenient. I also reorganized my daily and weekly schedules, so that it was no longer necessary to burn the midnight oil working on study assignments or other tasks. And finally, I picked up mindfulness meditation as a means to calm my racing thoughts before going to sleep—only much later would I become aware of the many other benefits of that practice. Of course, none of these things alone were an immediate game-changer, but taken together, their positive impact accumulated and made itself clear and tangible over time.

The point is: Overcoming my initial inertia was hard. But once I had proven to myself that I could change for the better, even in the smallest of doses, I was able to build a tiny bit of momentum. Then, over time, the benefits began to accumulate, even compound. For instance, regular exercise naturally leads to better sleep. Better sleep makes it easier to be mindful. More mindfulness increases awareness for what your body needs in order to function well. That awareness turns into an improved diet. A better diet pays off as it makes exercise more enjoyable. And so on, and so forth.

Conclusion

To sum it up, these questions of finding pleasure, creating sustainability, and overcoming inertia are not only extremely complex, but also deeply intertwined. Launching any kind of positive lifestyle change is hard, but doing it with patience and a low bar for expected outcome can make it a lot easier to get started—and to not be as hard on oneself in case it doesn’t go quite the way we envisioned. But in order to make any change stick, it’s crucial to transform it from an occasional activity that requires willpower into a regular, automatic habit—especially if your mind enjoys routine as much as mine. And finally, by turning to the Stoics, the Buddhists, or even modern-day thinkers like Albert Camus or Viktor Frankl, we can learn to readjust our sense of satisfaction in such a way, that even the most mundane activities spark joy.