At first it struck me as an exaggeration when James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, wrote the following in one of his recent newsletters:

“Most big, deeply satisfying accomplishments in life take at least five years to achieve. This can include building a business, cultivating a loving relationship, writing a book, getting in the best shape of your life, raising a family, and more.”

The more I think about it though, the more two things stand out about his point: First, how well it actually corresponds with my personal experience. And second, that it’s quite at odds with how we commonly think “success” works. But regardless if we’re talking about five years, as Clear does, or the 10,000 hours that Malcolm Gladwell identified in Outliers, the point is that perseverance always trumps intensity: Deliberate, goal-directed effort, applied consistently over a long stretch of time, and ideally with a feedback loop built in, is bound to yield lasting effects. But here’s the catch: While traveling along such path, the individual steps we take often look insignificant. Progress is thus hard to discern and the perceived lack thereof can easily discourage us from keeping at it.

Moreover, our culture abounds with heroic tales where the only discernible morale seems to be to idolize the exact opposite of perseverance: The narrative of many successful companies emphasizes that typical Silicon Valley blend of crunch culture and individual heroism much more than long-term aspirations and a sustainable way of working towards them. And its easy to see why this resonates with so many founders and entrepreneurs: If hard work is what’s required at all, then at least we want to see its effects play out instantaneously. Who has time to wait five years if the competition is at your back, the market is in turmoil, and the shareholders are out to get you?

The same, unfortunately, is true when it comes to leading an accomplished life: For instance, when I was growing up, casting shows on TV were a big thing. Thus, an entire generation of teenage girls and boys was led to believe that fame and fortune, and, alas, happiness, could be achieved instantly. That all that was required of you was natural talent and an opportunity to show off your inherent greatness to an awestruck audience. Nowadays, even the role of talent has diminished to such a degree that aspirations towards effortless careers, such as becoming an influencer on social media, have gained even greater popularity among the adolescent.

But perseverance, which is pretty much the opposite of the misguided idea that any kind of lasting success could be available straightaway through the application of some magic formula or brute force, comes with its own set of pitfalls. For one, it’s just harder for some people than for others to establish such formative habits in their life which will, over the long term, yield positive results. But while Clear and others have written at length about the importance of building routines to that end, even those who succeed in implementing them can easily get discouraged by a lack of visible progress.

Let me give you an example: Since I shed a couple of my less beneficial customs, including those of smoking and drinking, a few years ago, my “drug of choice” has become long-distance running. But while that activity lends itself nicely to statistical analysis, it’s surprisingly hard to appreciate one’s improvement over time subjectively. The reason why transformative progress in running is hardly ever felt is twofold: First, it happens at a truly glacial pace. Muscles, joints, tendons, and even bones do adapt to rising challenges in training but these adaptations take months or even years to unfold. Impatience, for that matter, is the leading cause of injuries among aspiring runners—trust me on that one. But secondly, my run this morning didn’t necessarily feel better than the one I did one year ago or two years ago because the difference in my physical ability is equally matched by a subconscious desire to run longer, or faster, or to attack ever more steep hills. Thus, the subjective experience continues to be the same, leaving me with the dull sense that I hadn’t made any progress at all. Here however, a bit of perspective can be of great help.

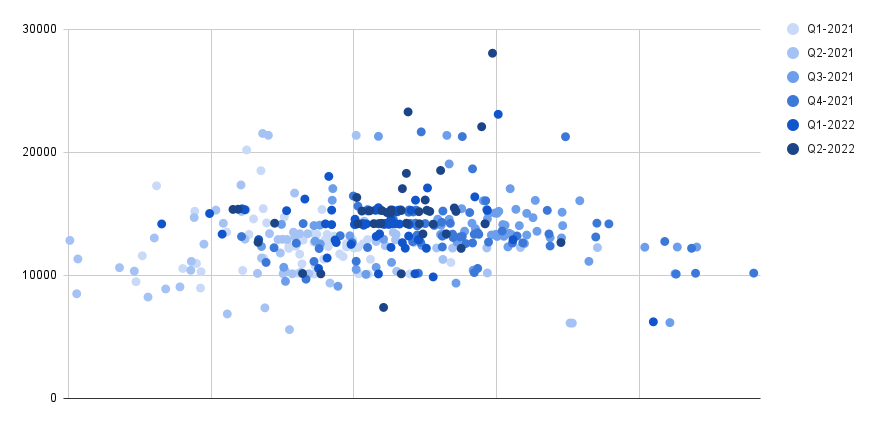

The graph below maps my runs between January 2021 and May 2022—about 370 activities in total. The color of each dot indicates the three month period in which the run occurred, the darker the shade, the more recent the run. On the x-axis you see the average speed of that run and on the y-axis the distance covered. Notice that, as the dots get darker and darker, they visibly cluster more on the top-right corner of the chart (that is, they’re longer and faster):

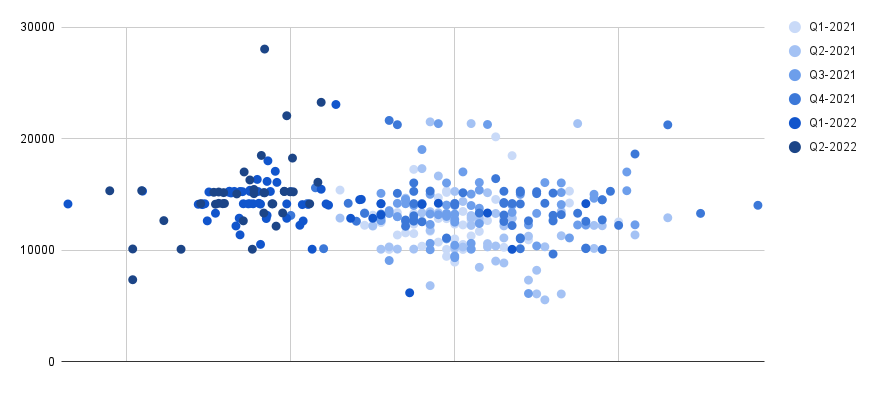

But the next plot is even more striking to me. It’s based on the same data, but shows the distance of each run compared with my average heart rate. The top-left corner holds long runs at low heart rate, while short ones with high heart rate cluster on the bottom-right. Clearly, my cardiovascular system has adapted significantly over the last couple of quarters, even though I hardly noticed these changes subjectively.

This effect is of course prevalent in many other fields of personal improvement: You won’t observe a sudden, overnight change in your writing skills despite a regular habit of journaling. Your ability to stay focused will not feel different all of a sudden even after years of meditation practice. But by at least trying to take the long-term view, by comparing oneself not with yesterday, but with one or five years ago, these improvements do make themselves known.

The same, as I’m not the first to point out, is true in business. Companies that are “built to last”, as James Collins and Jerry Porras put it, are based on a set of values very different from those which haphazardly stumble from one earnings call to the next, always on the lookout for shortcuts or quick-wins to please the shareholders.

Perseverance can feel futile at times. Sticking to something worthwhile, even if it doesn’t seem to pay off, can be hard. But if we manage to reframe our sense of time, as Clear advises, to look five years, not just five weeks, into the future (or the past for that matter), progress suddenly becomes visible where at a first glance everything looked bleakly stagnant.